DNA Diet Testing: What Works and What Doesn’t

Article at a Glance

- DNA Diets, also called nutrigenomics, are not a magic cure all, and sadly, some products have been oversold to the public.

- For example, using just a handful of genes to craft a short term weight loss regimen has proven ineffective.

- However, well designed studies which utilized polygenic risk scoring and had longer time horizons have shown tremendous promise for DNA diet interventions in weight loss, improved cholesterol and blood glucose numbers, and in adherence.

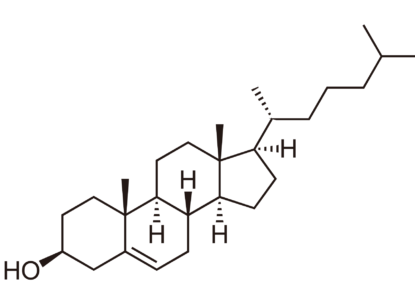

- From DNA methylation, to phytosterol and cholesterol absorption, to dietary fat metabolism, there is promising genetic research in many areas of nutrition. The task for our industry is to tie together these disparate “gene-diet interaction” nodes into a product that helps people eat in a way that truly moves the needle and makes them healthier over the long term.

Genes Mentioned

Contents

The first thing you need to know about “DNA dieting” is there is no one DNA diet.

DNA diets are designed by teams of scientists using different genetic markers, with different weighting based on the strength of the research for that gene. The analogy I like to use is to a mutual fund. All mutual funds are similar, they represent a basket of stocks hand picked by a fund manager with the goal of maximizing returns and mitigating risk. However, while these funds share a basic structure, not all mutual funds contain the same stocks (even if there is overlap with some blue chip stocks between funds).

The same principle applies to a polygenic risk score, which is a method for evaluating genetic risk based on the hundreds of SNPs, or gene “mutations.” Just as mutual funds are built using baskets of stocks, DNA diets are built using polygenic risk scores.

How we built our DNA diet test

At Gene Food, we designed our DNA diet product using an amalgamation of polygenic risk scores for:

- Dietary fat metabolism

- Saturated fat metabolism

- APOE status

- Histamine

- Lactose intolerance

- Carbohydrate metabolism

This is an algorithm we have been working on for more than seven years now and the customers who buy our product receive their diet type based on this scoring system. Some competing products evaluate many of the same genetic markers we look at, but the weights and the way the scores are formulated vary from company to company.

The Gene Food DNA diet is unlike any other product on the market. You could say we are a unique “nutrition fund.” The power of what we do is rooted in the sheer number of SNPs we score, a number which is always increasing as new research emerges, plus how we combine several polygenic risk scores to arrive at the core diet type.

This is why in some edge cases, a Gene Food user will see their diet type change to a closely aligned diet type based on the addition of a new SNP to the algorithm, or the increase (or decrease) in a given SNPs Science Score, which is our internal weighting model that we list next to each gene in the system.

Where DNA diets have fallen short, it is often the case that the studies looked at only 1-3 genes, which means the polygenic risk models were underpowered.

A study, highlighted by Dr. Peter Attia on his blog, found DNA diets were no more effective than “one size fits all” calorie restriction for weight loss looked at just 10 SNPs. That study lasted only 12 weeks. The BMC Nutrition Study I review below found efficacy for weight loss with a genetically tailored diet, but the results took 18 months!

To further illustrate the necessity of a diversified risk score, let’s dive into some basics.

Get Started With Personalized Nutrition

Gene Food uses a proprietary algorithm to divide people into one of twenty diet types based on genetics. We score for cholesterol and sterol hyperabsorption, MTHFR status, histamine clearance, carbohydrate tolerance, and more. Where do you fit?

SNP Testing vs. Genetic risk scoring

According to the Human Genome Project, the human genome has between 20,000 – 25,000 genes. As I referenced above, one of the core problems with “DNA diet” studies, as well as the reporting on them, is the failure to differentiate between the use of a single SNP vs. the use of an algorithm which factors in hundreds of SNPs.

A single nucleotide polymorphism, or “SNP,” is the most common type of genetic “mutation” found in people. We all have variants in shared genes which cause small changes in enzyme activity, or in the case of rare genetic disorders, the loss of function altogether. As a general rule, it is not a good idea to base dietary or supplement decisions on any one SNP.

Many SNPs, such as MTHFR, are common, and hyper-focusing on a mechanism out of context leads to error.

However, this doesn’t mean that SNPs aren’t important.

Just as we aim to diversify our stock portfolios, we should also take a pluralistic approach to SNPs and DNA diets.

Genetic risk scores (GRS), which are also called polygenic risk scores, have the potential to be more reliable than the current study of one SNP at a time. On its page about polygenic risk scores, The National Human Genome Institute does a fantastic job of explaining the difference between single gene vs. complex diseases. Most nutrigenomic markers standing alone don’t determine health outcomes in the same way that a single gene disease, as with cystic fibrosis. Rather than looking at just a handful of SNPs, algorithms like the one we have at Gene Food aggregate information from multiple risk related SNPs and assign a comprehensive score for a given macronutrient.

GRS will be a part of the future of personalized medicine and nutrition and studies are already showing that GRS has greater efficacy than just placing people on one size fits all diets like Keto.

Polygenic risk scoring is used by some of the country’s most advanced health systems and labs, including:

With that background out of the way, let’s dive into a deeper analysis of some of the DNA diet studies out there. For those who are interested, we also keep a table of some of noteworthy studies on our Science page.

BMC Nutrition nutrigenomics study

Researchers in the UK compared a ketogenic diet vs. a DNA tailored diet for maximum nutrition.

Although weight loss wasn’t the goal at the outset, body weight, total cholesterol, HDL, and fasting blood sugar were all measured. The 114 subjects were monitored in two stages: a 24 week initial stage and then an 18 month follow up.

The follow up after 18 months was put in place because it’s extremely difficult to lose weight and to keep it off. Many people who struggle with weight can follow a crash diet for a short period of time and have success, but long term the weight comes back. This was the pattern researchers found in this study.

Initially, members of the ketogenic diet group lost on average about 2.5 more kg than the nutrigenomic group, who were placed on a low glycemic index DNA diet similar to our Forager diet. However, the results after the 18 month follow up period were stunning.

After a year and a half, the weight loss for the DNA diet group was significantly higher than the ketogenic diet group, who saw significant weight gain after the 24 week sprint. After 18 months, the DNA diet group had lost on average 8 kg more than the ketogenic diet group. Further, the DNA diet group had significantly better results in lowering total cholesterol and fasting glucose, and in raising HDL.

The nutrigenomic group had better adherence than the ketogenic diet group and were given an exercise program tailored to their genetics as well. By contrast to the JAMA study cited by Scientific American which looked at only 3 SNPs, the BMC study evaluated 28 SNPs and 22 genes. We are familiar with the genes used in the BMC study because we use them in our algorithm and include them in our Guide to Nutrigenomics.

Notably, the BMC study increased dietary folate intake for those with MTHFR SNPs and gave them a B complex supplement with 400 mcg of folate (unclear whether methylfolate was given). The use of 28 SNPs to form a polygenic risk score, as opposed to trying to gauge outcomes from a single SNP, is a step in the right direction, and inevitably contributed to the success seen by the DNA diet group.

However, the BMC study again has the fatal flaw of a lack of diversity. All the participants here were European Caucasian. This is one of the most exciting nutrigenomics studies to be released to date, and the fact that it was published by BMC Nutrition, one of the best peer reviewed journals in the world, makes it all that much better.

Get Started With Personalized Nutrition

Gene Food uses a proprietary algorithm to divide people into one of twenty diet types based on genetics. We score for cholesterol and sterol hyperabsorption, MTHFR status, histamine clearance, carbohydrate tolerance, and more. Where do you fit?

Journal Circulation Study

This study, which appeared in the Journal Circulation, a publication under the auspices of the American Heart Association, found that variants in the IRS1 genes (specifically IRS1 rs2943641 CC genotype) can benefit from a higher carbohydrate and lower fat diet to combat insulin resistance.

The Circulation study evaluated 738 subjects over 2 years and saw improvements in both insulin levels and weight loss for those assigned to a DNA diet protocol.

For me, the Circulation study was particularly interesting because it may shed light on which genotypes can utilize plant based diet protocols to combat high blood sugar, and conversely, which people might do better using a lower carb approach to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

For those of us following the “diet wars,” this issue is on the front lines. Plant based doctors say the problem is always fat and low carb enthusiasts blame the carbs and sugar. Expansion of nutrigenomics research could help us better answer these questions for individuals, rather than operating under the current fiction that everyone can follow one diet.

MESA Trial and “Gene-Diet Interaction”

While some trials, like the one Peter Attia blogged about, have evaluated a handful of SNPs for weight loss and underwhelmed with results, there is growing buzz in the scientific community behind the concept of “gene-diet” interaction and personalized nutrition. For example, in its 2022 State of the Art Review, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology had this to say about when to strictly limit dietary saturated fats as a matter of policy:

In some cases, dietary SFAs enhance the association of genetic variants predisposing to increased CVD risk. This has been shown for the apo E (APOE) gene, one of the most extensively researched loci in relation to CVD risk. Specifically, carriers of the less common APOE4 allele have repeatedly shown greater fasting plasma lipid responses to saturated fat in the diet than do non-APOE4 carriers (76,77) and similar findings have been reported in the postprandial state (78). These gene by diet interactions have been demonstrated for other CVD risk factors as well, such as obesity.

Similarly, large scale trials like the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) have found additional gene-diet interactions, with the scope of the research hard to ignore. Specifically, MESA found:

- Individuals with less efficient FADS1 alleles may require preformed long-chain omega-3s (like EPA/DHA from fish) rather than relying on ALA (from flax/chia).

- Individuals with the APOE ε4 allele experience a greater increase in LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk when consuming diets high in saturated fat.

- TCF7L2 rs7903146 (the “farmer gene”) is one of the strongest genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes across populations.

- Carriers of the G allele for PPARGrs1801282 may have improved insulin sensitivity and lower diabetes risk with higher intake of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids (including vegetable oils), and higher risk when eating a high saturated fat diet. Essentially, the Ala variant (‘G’) creates a body that’s more “tuned” to thrive on polyunsaturated fats — and less forgiving with saturated fats.

DNA diets are not uniform

As you continue researching DNA diets, keep these issues in mind.

First, there is no one uniform DNA diet. The studies on efficacy are mixed and they almost exclusively look at weight loss rather than cardio-metabolic health. Most of these studies focus on only 2-3 genes.

A fair conclusion based on the scientific evidence available to us would be to say that DNA diets require more research, and they cannot solve for every health issue facing Americans.

But, as we all know, that type of headline doesn’t drive clicks and ad revenue. Saying DNA diets “don’t work” is like saying the election polling industry doesn’t work, or that there is no reason to test biomarkers like LDL-C because not everyone with elevated LDL-C will die of a heart attack, or that meteorology doesn’t work because the weather woman is occasionally wrong about when that nasty rain storm will hit.

DNA diets do work and their coverage in the clickbait science journalism world has been, well, unscientific. Just as election polling models, like Nate Silver developed at FiveThirtyEight, predict likely election outcomes, and just as LDL-C is a predictor of increased heart disease risk, and just as the weather woman uses meteorological tools to predict the weather, DNA diets, at least the good ones, are predictive tools that evaluate predispositions for a particular response to particular diet.

As the BMC study cited above demonstrates, any good DNA diet scoring system takes into account multiple SNPs and then scores people based on the latest research. The resulting score isn’t your fate, it’s a path towards lifestyle changes that can help avoid potential pitfalls based on genetic predispositions.

Gerald Dropped His LDL-C by 100 Points With Diet Alone

Gerald was an ultramarathon runner, but despite his dedication to fitness, he was struggling with rising cholesterol levels, increasing blood pressure, and low energy.